————

Part 1: GIDYQ-AA Personal Reflection

Part 2: Psychological Benefits of Diagnostic Confirmation

Part 3: Childhood Gender Non-Conformity

Part 4: DSM and ICD Diagnostic Criteria

~ Part 5 in the Gender Dysphoria Diagnosis series ~

————

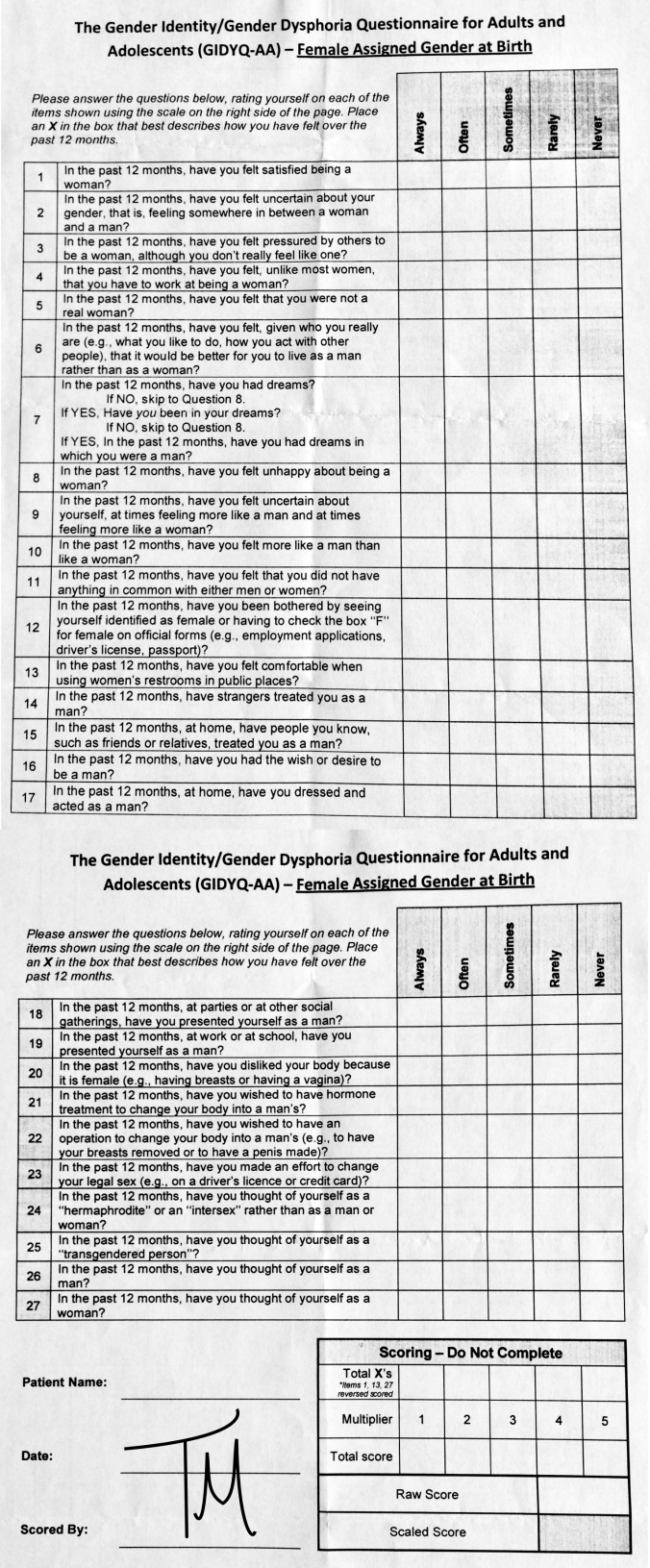

The most commonly viewed post on this blog is Part 1 of this series: GIDYQ-AA Personal Reflection. The popularity of this post likely reflects considerable curiosity regarding the diagnostic process for gender dysphoria. Part 1 only listed a handful of questions from the questionnaire in the context of my personal reflection. It is nearly impossible to find a complete version of the GIDYQ-AA online without access to scientific journals through academic servers, so I thought it might be helpful for readers to dedicate a post to the full text of the GIDYQ-AA.

Below, I have recorded the Female Assigned at Birth and Male Assigned at Birth versions of the GIDYQ-AA in their entirety. I created my own GIDYQ-AA documents formatted for printing, including a table to record responses to questions and a section for scoring; these documents are available for download. I also have a section describing the scoring process in detail. Finally, abstracts from the study describing initial development of the GIDYA-AA (Deogracias 2007) and from a study providing further evidence to support the validity of the GIDYQ-AA (Singh 2010) are also included.

————

GIDYQ-AA Documents for Download

Female Assigned at Birth (Adult) Word

Female Assigned at Birth (Adult) PDF

Female Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) Word

Female Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) PDF

Male Assigned at Birth (Adult) Word

Male Assigned at Birth (Adult) PDF

Male Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) Word

Male Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) PDF

————

GIDYQ-AA (Female Assigned at Birth) Full Text

Response options are “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never.” Items 1, 13, and 27 were reversed scored. For adolescents < 18 years of age, the word woman was changed to girl. Items 1-2, 5-10, 16, and 24-27 were considered to be subjective indicators of gender identity/gender dysphoria. Items 3-4, 11, 13-15, and 17-19 were considered social indicators. Items 20-22 were considered somatic indicators. Items 12 and 23 were considered sociolegal indicators.

01. In the past 12 months, have you felt satisfied being a woman?

02. In the past 12 months, have you felt uncertain about your gender, that is, feeling somewhere in between a woman and a man?

03. In the past 12 months, have you felt pressured by others to be a woman, although you don’t really feel like one?

04. In the past 12 months, have you felt, unlike most women, that you have to work at being a woman?

05. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you were not a real woman?

6. In the past 12 months, have you felt, given who you really are (e.g., what you like to do, how you act with other people), that it would be better for you to live as a man rather than as a woman?

07. In the past 12 months, have you had dreams? If NO, skip to Question 8.

If YES, Have you been in your dreams?

If NO, skip to Question 8. If YES, In the past 12 months, have you had dreams in which you were a man?

08. In the past 12 months, have you felt unhappy about being a woman?

09. In the past 12 months, have you felt uncertain about yourself, at times feeling more like a man and at times feeling more like a woman?

10. In the past 12 months, have you felt more like a man than like a woman?

11. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you did not have anything in common with either men or women?

12. In the past 12 months, have you been bothered by seeing yourself identified as female or having to check the box “F” for female on official forms (e.g., employment applications, driver’s license, passport)?

13. In the past 12 months, have you felt comfortable when using women’s restrooms in public places?

14. In the past 12 months, have strangers treated you as a man?

15. In the past 12 months, at home, have people you know, such as friends or relatives, treated you as a man?

16. In the past 12 months, have you had the wish or desire to be a man?

17. In the past 12 months, at home, have you dressed and acted as a man?

18. In the past 12 months, at parties or at other social gatherings, have you presented yourself as a man?

19. In the past 12 months, at work or at school, have you presented yourself as a man?

20. In the past 12 months, have you disliked your body because it is female (e.g., having breasts or having a vagina)?

21. In the past 12 months, have you wished to have hormone treatment to change your body into a man’s?

22. In the past 12 months, have you wished to have an operation to change your body into a man’s (e.g., to have your breasts removed or to have a penis made)?

23. In the past 12 months, have you made an effort to change your legal sex (e.g., on a driver’s licence or credit card)?

24. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a “hermaphrodite” or an “intersex” rather than as a man or woman?

25. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a “transgendered person”?

26. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a man?

27. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a woman?

————

GIDYQ-AA (Male Assigned at Birth) Full Text

Response options are “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never.” Items 1, 13, and 27 were reversed scored. For adolescents < 18 years of age, the word man was changed to boy. Items 1-2, 5-10, 16, and 24-27 were considered to be subjective indicators of gender identity/gender dysphoria. Items 3-4, 11, 13-15, and 17-19 were considered social indicators. Items 20-22 were considered somatic indicators. Items 12 and 23 were considered sociolegal indicators.

01. In the past 12 months, have you felt satisfied being a man?

02. In the past 12 months, have you felt uncertain about your gender, that is, feeling somewhere in between a man and a woman?

03. In the past 12 months, have you felt pressured by others to be a man, although you don’t really feel like one?

04. In the past 12 months, have you felt, unlike most men, that you have to work at being a man?

05. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you were not a real man?

06. In the past 12 months, have you felt, given who you really are (e.g., what you like to do, how you act with other people), that it would be better for you to live as a woman rather than as a man?

07. In the past 12 months, have you had dreams? If NO, skip to Question 8.

If YES, Have you been in your dreams?

If NO, skip to Question 8.

If YES, In the past 12 months, have you had dreams in which you were a woman?

08. In the past 12 months, have you felt unhappy about being a man?

09. In the past 12 months, have you felt uncertain about yourself, at times feeling more like a woman and at times feeling more like a man?

10. In the past 12 months, have you felt more like a woman than like a man?

11. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you did not have anything in common with either women or men?

12. In the past 12 months, have you been bothered by seeing yourself identified as male or having to check the box “M” for male on official forms (e.g., employment applications, driver’s license, passport)?

13. In the past 12 months, have you felt comfortable when using men’s restrooms in public places?

14. In the past 12 months, have strangers treated you as a woman?

15. In the past 12 months, at home, have people you know, such as friends or relatives, treated you as a woman?

16. In the past 12 months, have you had the wish or desire to be a woman?

17. In the past 12 months, at home, have you dressed and acted as a woman?

18. In the past 12 months, at parties or at other social gatherings, have you presented yourself as a woman?

19. In the past 12 months, at work or at school, have you presented yourself as a woman?

20. In the past 12 months, have you disliked your body because it is male (e.g., having a penis or having hair on your chest, arms, and legs)?

21. In the past 12 months, have you wished to have hormone treatment to change your body into a woman’s?

22. In the past 12 months, have you wished to have an operation to change your body into a woman’s (e.g., to have your penis removed or to have a vagina made)?

23. In the past 12 months, have you made an effort to change your legal sex (e.g., on a driver’s licence or credit card)?

24. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a “hermaphrodite” or an “intersex” rather than as a man or woman?

25. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a “transgendered person”?

26. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a woman

27. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a man?

————

————

GIDYQ-AA Scoring

The table at the bottom of the photo above shows how the questionnaire is scored. The scoring process is the same for the female-assigned-at-birth and the male-assigned-at-birth versions. I have summarized the scoring process in more detail below.

- Participant fills out the questionnaire, indicating how often each question applies to them (“always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never”).

- The number of X’s in each category (“always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “never”) are added up. Items 1, 13, and 27 are reversed scored, which means that for those questions, an “always” response would actually be counted as “never” and an “often” response would actually be counted as “rarely.”

- The total number of responses in each category (including reverse scored items) are then multiplied by weighting factors: the number of “always” responses is multiplied by 1, the number of “often” responses is multiplied by 2, the number of “sometimes” responses is multiplied by 3, the number of “rarely” responses is multiplied by 4, and the number of “never” responses is multiplied by 5.

- The multiplied totals for each category are then added together to give the Raw Score.

- The Raw Score is then divided by 27 to give the Scaled Score. (Note: if participants left any items blank, the Raw Score is divided by the total number of items completed. For example, if a participant did not respond to 2 of the items on the questionnaire, the Raw Score would be divided by 25 instead of by 27 to give the Scaled Score).

Based on published studies evaluating the GIDYQ-AA, a Scaled Score less than 3.0 is strongly suggestive of gender dysphoria, while a Scaled Score greater than 3.0 is more likely to reflect the absence of gender dysphoria. However, no single questionnaire or scoring system can perfectly capture all of the variation in gender identity and personal goals (and I have previously discussed many of the problems that I think may interfere with the utility of the questionnaire), so scores on the GIDYQ-AA are not necessarily definitive and should not replace each individual’s sense of their own identity.

————

“The present study reports on the construction of a dimensional measure of gender identity (gender dysphoria) for adolescents and adults. The 27-item gender identity/gender dysphoria questionnaire for adolescents and adults (GIDYQ-AA) was administered to 389 university students (heterosexual and nonheterosexual) and 73 clinic-referred patients with gender identity disorder. Principal axis factor analysis indicated that a one-factor solution, account ing for 61.3% of the total variance, best fits the data. Factor loadings were all >.30 (median, .82; range, .34-96). A mean total score (Cronbach’s alpha, .97) was computed, which showed strong evidence for discriminant validity in that the gender identity patients had significantly more gender dysphoria than both the heterosexual and nonheterosexual university students. Using a cut-point of 3.00, we found the sensitivity was 90.4% for the gender identity patients and specificity was 99.7% for the controls. The utility of the GIDYQ-AA is discussed.” (abstract, Deogracias 2007)

“This study aimed to provide further validity evidence for the dimensional measurement of gender identity and gender dysphoria in both adolescents and adults. Adolescents and adults with gender identity disorder (GID) were compared to clinical control (CC) adolescents and adults on the Gender Identity=Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults (GIDYQ–AA), a 27-item scale originally developed by Deogracias et al. (2007). In Study 1, adolescents with GID (n1⁄444) were compared to CC adolescents (n1⁄498); and in Study 2, adults with GID (n1⁄441) were compared to CC adults (n1⁄494). In both studies, clients with GID self-reported significantly more gender dysphoria than did the CCs, with excellent sensitivity and specificity rates. In both studies, degree of self-reported gender dysphoria was significantly correlated with recall of cross-gender behavior in childhood—a test of convergent validity. The research and clinical utility of the GIDYQ–AA is discussed, including directions for further research in distinct clinical populations.” (abstract, Singh 2010)

————

References

Deogracias JJ, Johnson LL, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, et al. The Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. 2007. The Journal of Sex Research 44(4):370-79.

Singh D, Deogracias J, Johnson LL, et al. The Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults: further validity evidence. 2010. The Journal of Sex Research 47(1): 49-58.

I have some questions about the scoring of this questionnaire. Is there a key that accompanies the measurement tool, which indicates the individual’s diagnosis or level of dysphoria, based upon their score?

Also, is this tool in use anywhere, or available for sale/use?

LikeLike

Hi Jennifer,

Thank you for your questions. This post includes photos of the female-assigned-at-birth version of the GIDYQ-AA, which I was given during an initial assessment with a psychiatrist who specializes in gender dysphoria. At the bottom of the second photo is a table showing how the questionnaire is scored (the scoring process is the same for the female-assigned-at-birth and the male-assigned-at-birth versions). I have summarized the scoring process in more detail below. I may also update the original post to include this information.

GIDYQ-AA Scoring:

Step 1. Participant fills out the questionnaire, indicating how often each question applies to them (“always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never”).

Step 2. The number of X’s in each category (“always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “never”) are added up. Items 1, 13, and 27 are reversed scored, which means that for those questions, an “always” response would actually be counted as “never” and an “often” response would actually be counted as “rarely.”

Step 3. The total number of responses in each category (including reverse scored items) are then multiplied by weighting factors: the number of “always” responses is multiplied by 1, the number of “often” responses is multiplied by 2, the number of “sometimes” responses is multiplied by 3, the number of “rarely” responses is multiplied by 4, and the number of “never” responses is multiplied by 5.

Step 4. The multiplied totals for each category are then added together to give the Raw Score.

Step 5. The Raw Score is then divided by 27 to give the Scaled Score. (Note: if participants left any items blank, the Raw Score is divided by the total number of items completed. For example, if a participant did not respond to 2 of the items on the questionnaire, the Raw Score would be divided by 25 instead of by 27 to give the Scaled Score).

Based on published studies evaluating the GIDYQ-AA, a Scaled Score less than 3.0 is strongly suggestive of gender dysphoria, while a Scaled Score greater than 3.0 is more likely to reflect the absence of gender dysphoria. However, no single questionnaire or scoring system can perfectly capture all of the variation in gender identity and personal goals (and I have previously discussed many of the problems that I think may interfere with the utility of the questionnaire), so scores on the GIDYQ-AA are not necessarily definitive and should not replace each individual’s sense of their own identity.

Published studies about the GIDYQ-AA do not distinguish the “severity” or “level” of gender dysphoria based on GIDYQ-AA score. Although a Scaled Score less than 3.0 is strongly suggestive of gender dysphoria, it has not been established, for example, that a score of 1.5 necessarily indicates more severe or intense gender dysphoria than a score of 2.9.

I am not sure to what extent the GIDYQ-AA is in use in various personal or medical contexts in different countries. As I have described in other posts, my assessment with a psychiatrist who specializes in working with transgender people involved completion of this questionnaire (I live in Alberta, Canada). Similar assessments by other specialists in other cities/countries may or may not involve the GIDYQ-AA.

The journal articles describing development of the GIDYQ-AA are not accessible for most online users, and I was frustrated that the questionnaire itself did not seem to be available in its entirety to the general public (for free or for sale). I have published complete versions of the GIDYQ-AA on my blog in order to make it available to a wider audience, especially for personal use.

I hope this information makes sense! If you have any other questions, or if you would like further explanation of the GIDYQ-AA scoring system, please let me know.

TomCat

LikeLike

Thank you for your prompt and thorough response, Tom. I’ve been looking for an assessment tool to use in my practice with young adults, and I think this may fit the bill, while acknowledging that many folks’ (including my own) conceptualization of gender is not binary and this tool is somewhat limited in that respect. I do think it fits into a very medicalized framework of gender, and it is most often medical professionals with whom I am called upon to advocate, on my clients’ behalf.

If you know of another tool you’d recommend over this one, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

LikeLike

Although the GIDYQ-AA does have limitations (as does any questionnaire or set of diagnostic criteria), it seems like a potentially useful assessment tool in clinical settings… it provides a quick, objective, and scientifically validated means of scoring a very complex and subjective experience. GIDYQ-AA scores can be reassuring for individuals questioning their gender identity (confirming their own suspicion of gender dysphoria) and the scores can add legitimacy to a clinician’s diagnosis when communicating with colleagues. So it sounds like this tool would fit well with your practice, particularly when advocating on clients’ behalf with medical professionals.

Many different questionnaires have been published to assess gender identity, gender dysphoria, and/or transsexualism. However, most of these questionnaires are several decades old and therefore reflect very outdated concepts of gender. Considerable progress in medical/surgical transition options and increased understanding of non-binary concepts of gender mean that many of the older questionnaires are no longer relevant. The GIDYQ-AA (developed in 2007) and the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS) (developed in 1996) are two of the most recent and most commonly used tools for assessment of gender dysphoria. A recent article (Schneider 2016) compared the GIDYQ-AA and the UGDS on a population of 318 gender dysphoric individual presenting to European gender identity clinics.

UGDS is a 12-item questionnaire with responses categorized in terms of degree of agreement with item statements (ie. agree completely, agree somewhat, neutral, disagree somewhat, disagree completely). Each item is scored from 1-5. Total scores range from 12 – 60, with higher scores indicating more severe gender dysphoria. A cut-off score of 40 was established to distinguish gender dysphoric from non-gender-dysphoric populations (scores above 40 suggest that gender dysphoria is present). The UGDS in it’s entirety is below.

Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (Female-to-Male Version)

Response categories are agree completely, agree somewhat, neutral, disagree somewhat, disagree completely. Items 1, 2, 4–6, and 10–12 are scored from 5 to 1; Items 3 and 7–9 are scored from 1 to 5.

(1) I prefer to behave like a boy.

(2) Every time someone treats me like a girl I feel hurt.

(3) I love to live as a girl.

(4) I continuously want to be treated like a boy.

(5) A boy’s life is more attractive for me than a girl’s life.

(6) I feel unhappy because I have to behave like a girl.

(7) Living as a girl is something positive for me.

(8) I enjoy seeing my naked body in the mirror.

(9) I like to behave sexually as a girl.

(10) I hate menstruating because it makes me feel like a girl.

(11) I hate having breasts.

(12) I wish I had been born as a boy.

Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (Male-to-Female Version)

Response categories are agree completely, agree somewhat, neutral, disagree somewhat, disagree completely. Items are all scored from 5 to 1.

(1) My life would be meaningless if I would have to live as a boy.

(2) Every time someone treats me like a boy I feel hurt.

(3) I feel unhappy if someone calls me a boy.

(4) I feel unhappy because I have a male body.

(5) The idea that I will always be a boy gives me a sinking feeling.

(6) I hate myself because I’m a boy.

(7) I feel uncomfortable behaving like a boy, always and everywhere.

(8) Only as a girl my life would be worth living.

(9) I dislike urinating in a standing position.

(10) I am dissatisfied with my beard growth because it

makes me look like a boy.

As I described in my post, the GIDYQ-AA is a 27-item questionnaire with responses categorized in terms of frequency that item statements apply (ie. always, often, sometimes, rarely, never). Each item is scored from 1-5. Mean score is calculated from responses to all items, so the final scaled score ranges from 1 – 5, with lower scores indicating with more severe gender dysphoria. A cut-off score of 3.0 was established to distinguish gender dysphoric from non-gender-dysphoric populations (scores lower than 3.0 suggest that gender dysphoria is present).

These two questionnaires capture slightly different aspects of gender dysphoria. The UGDS focuses on dissatisfaction with physical attributes, gender identity, and gender roles. The GIDYQ-AA focuses on subjective, physical, social, and sociolegal aspects of gender dysphoria. UGDS questions do not specify a time frame, while GIDYQ-AA questions focus on the previous 12 months. In the comparison study, UGDS responses indicated proportionally higher gender dysphoria scores than GIDYQ-AA responses, particularly for FTMs; this finding may be partially related to the lack of specified timeframe in UGDS questions compared to GIDYQ-AA (thinking about a more limited timeframe may reduce an individual’s subjective assessment of dysphoria intensity/severity), and may be partially related to the ceiling effect in the female version of the UGDS (nearly 1/3 of FTMs reached the maximum score of 60) which can artificially decrease correlations between measurement instruments.

Given that information, it seems like either the UGDS or the GIDYQ-AA (or both) could be useful in the clinical situation you describe. However, I think the GIDYQ-AA captures more aspects of dysphoria and reflects a more inclusive non-binary gender concept compared to the UGDS. I think the GIDYQ-AA may also be more valuable for FTMs in particular, because it does not have the ceiling effect observed with the UGDS. Of course, the caveat is that I have no formal training in this area (I am not a counsellor or physician) and I have formed these opinions based on review of published literature and my own personal experience.

The way my blog post is written, I realized that it could be difficult to extract the GIDYQ-AA in a useable format. If you do decide to use this questionnaire, I’ve provided links below to documents with the GIDYQ-AA questionnaire formatted for printing and easy scoring (I’ve added brief comments on the forms about how to calculate the scaled scores, which will hopefully be more helpful than the photos of the original document that I posted). I may update my post to include these links. I’ve also included links below to the full text of the original GIDYQ-AA studies (Deogracias 2007 and Singh 2010) and the recent study comparing GIDYQ-AA with UGDS (Schneider 2016) if you are interested in further reading.

Reference Articles

Deogracias 2007

Singh 2010

Schneider 2016

GIDYQ-AA Forms

Female Assigned at Birth (Adult) Word

Female Assigned at Birth (Adult) PDF

Female Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) Word

Female Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) PDF

Male Assigned at Birth (Adult) Word

Male Assigned at Birth (Adult) PDF

Male Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) Word

Male Assigned at Birth (Adolescent) PDF

I hope this answers your questions! If you have any other questions (about any gender-related topics!), feel free to post comments here or send me an email at thomasingenderland@gmail.com.

LikeLike

Hello,

I am doing a class presentation on Gender Dysphoria and seeking permission to utilize your GIDYQ-AA forms for my PowerPoint presentation and case study. Please let me know at your earliest convenience if permission is granted. Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Kayla,

Feel free to use those forms in your presentation. Thanks for asking for my permission!

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

I want to thank you for sharing your experience. I am a mom of a gender nonconforming eleven year old child who feels to me like part of your gender-tribe. We are about to embark on a journey to decide whether or not to medically slow down puberty. Your story helps me a lot, as you are a few years ahead of my child–and I can see already that my kiddo is similarly formulating her own puberty-stall, in the form of exercise, diet, etc to slow the arrival of breasts in particular. I’m so grateful to you for sharing your experience. And one of the things that is sparking around in my head right now is that if they child is planning their own version of puberty avoidance, there is a “there” there, even though there has never been a formal, outright plea for becoming a different gender entirely. Thanks for your brave and thoughtful sharing.

LikeLike

Hi Cristina,

I’m so glad that my blog has been helpful for you. It sounds like you and your child are approaching a very important – and potentially very difficult – decision about whether to pursue medical puberty suppression.

My own experience certainly aligns with your suspicion that a child’s attempts to suppress puberty through diet and exercise may reflect underlying gender dysphoria, even in the absence of direct statements expressing a desire to transition. As a teenager, I was not aware that medical puberty suppression options existed. In hindsight, I believe that delaying puberty under medical supervision with parental support would have considerably reduced my disordered eating behavior (disordered eating which remains a daily challenge for me more than 10 years later). Although I may ultimately have chosen not to pursue cross-sex hormone therapy following puberty suppression, delaying those unwanted physical changes would have given me time to make an informed decision without becoming so preoccupied by starving away all traces of femininity.

Of course, this is a deeply personal decision, and what I believe would have been best for my teenage self may not be the best for others considering these options. I wish you the best of luck in making that decision. If you have any questions for me – about my own experience, or about research and other resources on these topics – feel free to leave a comment here or email me at thomasingenderland@gmail.com.

TomCat

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

Thanks a lot for the information supplied here.

I am an undergraduate student and I am currently carrying out an exploratory study on the prevalence of Gender Dysphoria in a culture-bound society, using adolescent undergraduates as a sample. I recently distributed the questionnaire provided here but I’m somewhat confused about how to analyse the results.

LikeLike

Hi Lei,

I’m glad the GIDYQ-AA has been useful for your study. The linked documents all include a table at the end of the questionnaire to guide scoring, and my original post includes a section called “GIDYQ-AA Scoring” which outlines the scoring process in more detail. I’m happy to provide further advice regarding questionnaire scoring, if you can send me specific questions…

Tom

LikeLike

Very helpful. Clearly written and thorough

explanations.

Thank you

LikeLike

Very useful information

Thank you

LikeLike

Very useful information

Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Tom, just want to ask for your permission. we’re currently conducting undergraduated thesis, can we used this test for qualification purposes of our participants?

LikeLike

Hello! Yes, you may use this test as part of your study protocol. I am not the original author of the test (references are provided in my blog post).

LikeLike

hello, do you know, if there is a german translation of that test?

LikeLike

Hello, I’m not sure whether there is a German translation of this test.

LikeLike

Hi,

First of all, thank you for all this deatiled information!

I know this post is quite old, but I just stumbled across it and would like to point something out. The questionnaire you present here was, as far as I know, developed for and used in a study, for research. As far as I am aware, such questionnaires can possibly be used in a diagnostic setting as a further tool get a better picture, say, togher with an interview, but an official diagnostic questionnaire must be standardized, reliable, valid, normed, and documented, with evidence showing it accurately identifies or measures the condition in question. Tools designed for research or screening may inform, but they cannot replace officially validated diagnostic instruments. I have heard of and read here of situations where this reasearch tool has been used for diagnsotics. I personally know of a case where it was used as the only diagnostic tool for gender dysphoria (the other tools being IQ-Test, attention,…).

I find this more than concerning. There are official, standardized questionnaires that can be used, with proper scoring key and interpretation guide.

There is an adapted German version, also solely for research, used for a study in a dissertation, that has also been used for diagnostics.

I state again, I find this very concerning.

What’s your opinion?

LikeLike